Base Phase: Putting in the MilesStatus: Been through build-up, preparing for future races

Goal: Able to run 5 to 7 days a week, average from 6 to 10 hours a week (and building a foundation for more in the future)

Duration of Base Phase: A few weeks to several months

Purpose of Build-up Phase: The base phase is more or less a continuation of the base build-up, in fact these can be seen as a continuum rather than discrete phases. The main objective is to build up training time to improve aerobic capacity while progressively mixing faster running to prepare for upcoming racing

The Base Phase is Perhaps the Most Neglected and Most Misunderstood of the Phases: I’ve been guilty of this myself, many times over. After a few months of build-up, you are feeling good and the temptation is start thinking about next week’s 5K and next month’s 10K and to jump into race specific training too soon. What you should do is be patient and think about those 5K, 10Ks, half marathons three to six months ahead. A little bit of racing is fine, but maybe a training race once a month with little or no race specific training.

Another misunderstanding is that the base phase is just going out and slogging long slow runs. Actually there is a lot of room for a little bit of speed, not to mention running at varied (usually aerobic) paces, including tempo and progression running.

Finally, hill running: yes or no? Some coaches and programs insist that hill running and hill repetitions are a necessary component during base phase, while others do not incorporate hill running. Lydiard himself, the original advocate, suggested hill running only some of the time, no more than two days out of the week. Again, it depends.

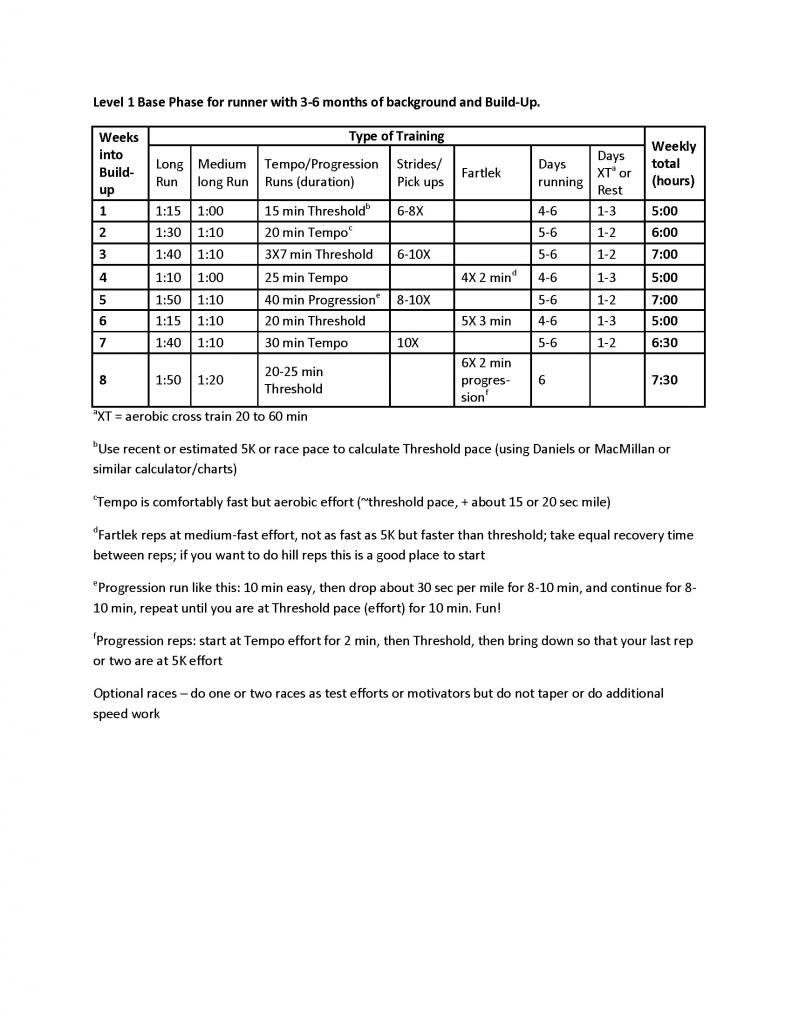

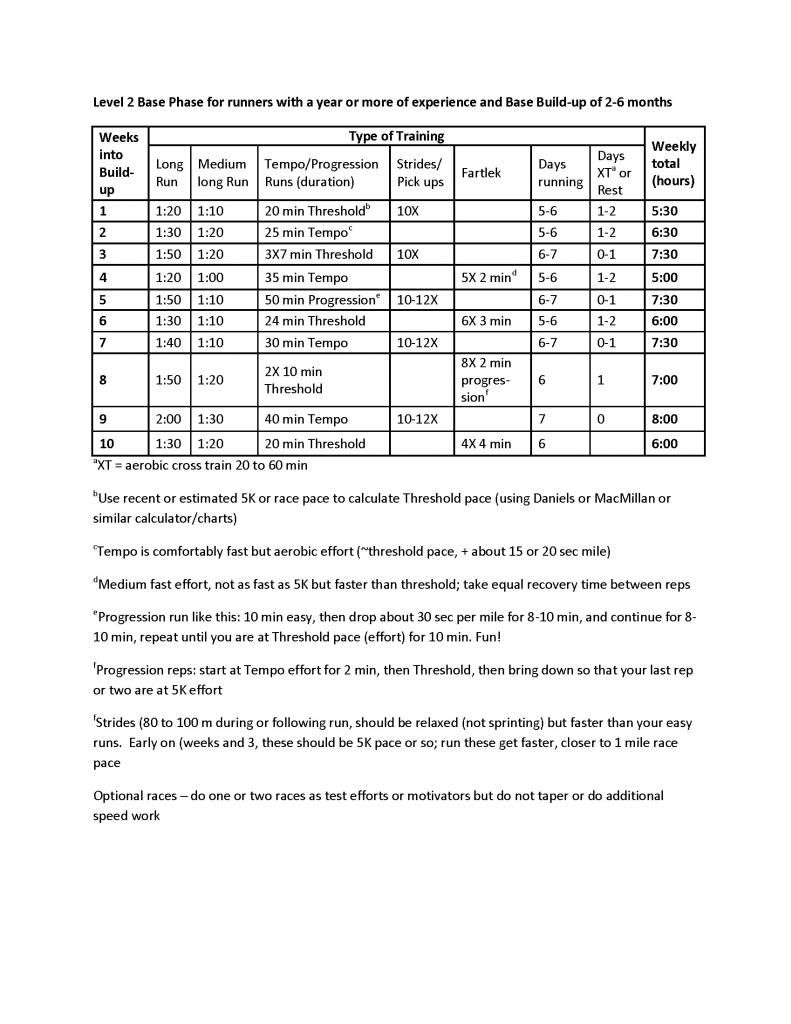

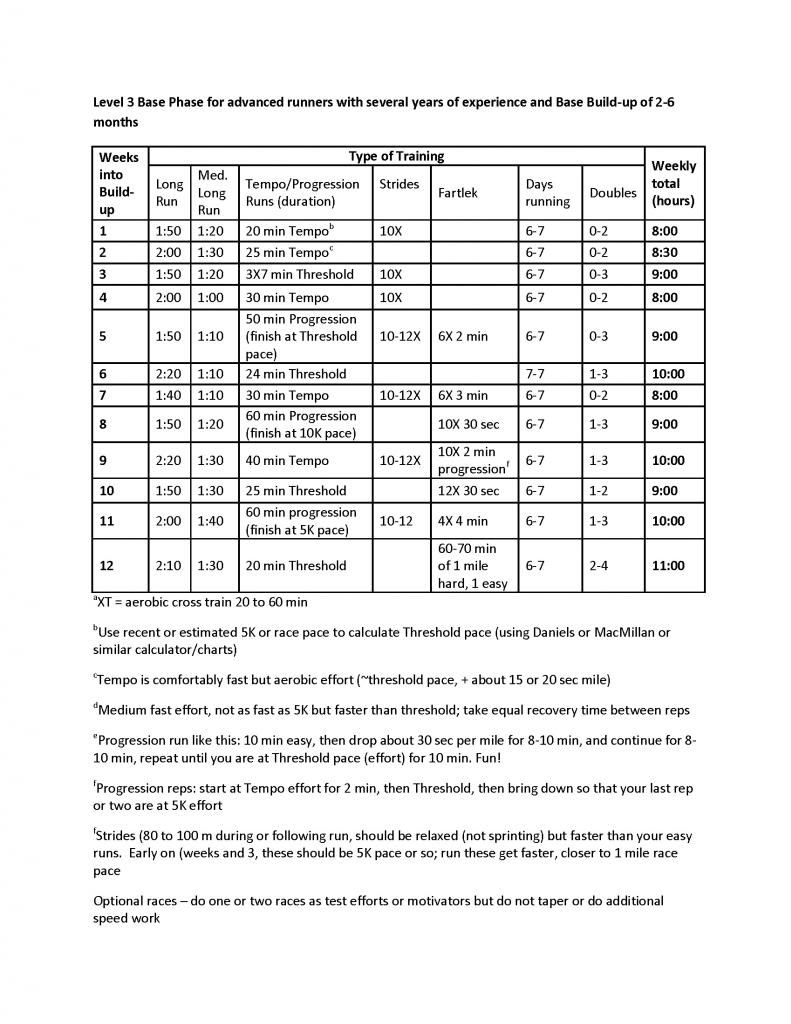

Let’s Get Out and Run!There are three example schedules below, and they more or less progress from the schedules listed from the Build-up phase. The first one is for the relatively new runner, the second one might be well suited for a seasoned runner who has trained consistently for a year or two, while the third schedule is for the more experienced/advanced runner.

We bring in several additional types of running, common vernacular to long-time runners, but perhaps new to the relative beginner. These are briefly defined in the footnotes of the tables, but could probably use a little more discussion here.

Tempo and

Threshold runs were introduced in the Build Up discussion. These are often used interchangeably and indeed a Threshold run is a form of Tempo running.

Threshold is short for lactate threshold, which is the intensity at which lactate builds in your body more rapidly than it can be processed. If you are racing you can hold this effort for about 1 hour. And if you have raced some recently, your lactate threshold is about 20 to 30 seconds per mile slower than your current 5K pace. There are numerous books, charts, and online calculators that can help you estimate your threshold pace. Typically you are aiming for about 20 to 25 minutes threshold in a given workout. Less than that and you’re not getting full benefit. More and you’re building up more lactate and getting into race effort, which you want to save for the races themselves. These can be broken up into shorter segments (repetitions with recovery intervals) or continuous. Finally, as you get into better shape your threshold pace will drop, which means you can start running faster, but be aware run at your best estimate of current threshold pace, not your goal pace—otherwise you risk getting into race effort too soon.

The definition for Tempo runs is more generic. In a broad context I see tempos (note small case) as sustained or effort greater than about 15 minutes up to 2 hours, ranging from about 10K pace to Marathon Pace. For the purpose of this little discussion Tempo (large case) pace is in that broad range, slower than Threshold pace, but faster than Marathon Pace. Physiologist/coach/author Jack Daniels even has charts that provide tempo paces of different duration. For example, a 20 min 5K runner has a threshold pace of 6:51 per mile, and the recommendation would be for that runner to do a 20 min threshold run at that pace. But that same runner would run at 7:00 pace for 30 minutes, or 7:05 for 40 minutes. In a workout sense the physiological outcome isn’t quite the same, but there is a time and place for each and in the Base Phase of training both have value and alternating these can be a good way to break things up.

Fartlek or speedplay is a great way to introduce some race-effort running without the pressure and stress of running for time on the track or over a measured distance. The goal in these workouts is to get your legs used to running at race efforts, but also at a substantially reduced duration. I like to start out with these after several weeks of aerobically-based running. Something around current Threshold to 10K race effort is a good place to start these. There is no limit to the combination of time and recovery, but I like to begin at reps of 2 or 3 minutes with equal recovery (jogging in between).

Progression Runs take a fair amount of concentration and, depending at what pace you’re finishing at, can be very challenging. But these can be fun and great confidence boosters, and if you’re open to the idea of listening to your body (not just a stop watch and Garmin), they can teach you a lot about pacing and effort. By doing these you can learn to feel your way to better training and racing. A progression run for our 20 min 5K runner might go like this: warm up 10 at 9 min/mile pace, and then bring it down about 30 sec/mile every 10 minutes. So their initial 40 min Progression Run would be 8:30, 8:00, 7:30, and 7:00. Next time try 50 minutes, but bring it down to 6:50 for the last 10 minutes. And so on. Advanced runners might try finishing with a mile at 5K pace. Killer!

To

Hill Run or not to

Hill Run? As I discussed that above, and it’s up to you. The fartlek repetitions are a good place to introduce hill running if that’s your thing.

Where From Here? By the end of this phase (sometimes middle, sometimes extended) you are ready to take on just about any distance from the 800 meters up to marathon and even beyond, and we'll get to those later. Meanwhile, what about the future? This is where the 10% rule can come in handy. Next time you embark on your base--provided you've gotten enough rest while not out of shape--add 10% or so onto your average and peak volume weeks during Base Phase. So if you maintained 7 hours, then try for an average of 7:45 to 8 hours next time, or if you were at 10, then go for 11. It's that aerobic progression over a number of years that will take you to heights you never thought imaginable.

[Finally, once again, the schedules are more for example purposes, so don’t get too caught up in following these exactly]